Pragmatism, Partnerships, and Persuasion: theorizing philanthropic foundations in the global policy agora

by Janis Petzinger

What actors or organisations bring international policy to life? Typically, one assumes that ‘policy work’ is enacted by and synonymous with ‘government work’. However, as we live in an increasingly globalised world, scholars of global policy and transnational administration have argued that we should see policy making as akin to the ancient Greek ‘agora’ – a marketplace of ideas that brings together diverse players from across the public, private, and nonprofit sectors that spread policy ideologies, collaborate and compete on policy projects, and contribute resources to the governance of global policies.

Here, a recognition of philanthropy’s influence on global policy has big implications for those of us that study the organisational phenomenon of foundations. Our paper, ‘Pragmatism, Partnerships, and Persuasion: theorizing philanthropic foundations in the global policy agora’, explores how institutional philanthropy operates within the changing global policy sphere. Featured in Policy and Society’s Special recently published special issue (titled Global Policy and Transnational Administration: Non-State Power, Authority, and Legitimacy), we propose a novel way of theorizing philanthropic foundations that can help us interpret, justify, and critique their organisational work.

Empirically significant, yet conceptually vague, the term ‘philanthropic foundation’ is somewhat of an empty signifier. It has no concrete legal definition in the US or UK (not to mention the frequently inconsistent definitions found around the rest of the world); it can do radically different types of organisational work (grantmaking, operating, fundraising); and it can take on varying forms of financing (via market-tied endowments, donations, or selling goods or services). Diverse views on their relationship to power further vexes our understanding of foundations, with some arguing that they are inherently undemocratic institutions (operating as ‘warehouses of wealth’)1, while others romanticise their good will at face value (operating as what John D Rockefeller Sr called ‘the business of benevolence’)2.

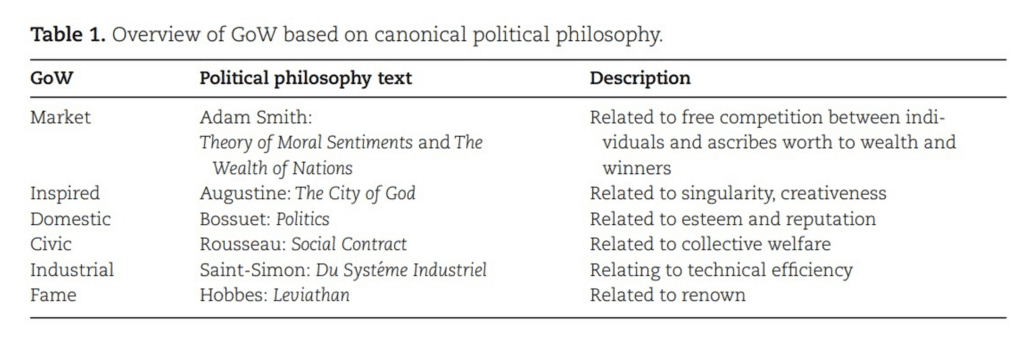

To address these epistemological issues, we offer French Pragmatic Sociology of Critique (FPSC) to analyse foundations’ work in the global policy arena. A non-structuralist, post-Bourdesian approach to sociology, this theory assumes that actors and organisations act pragmatically as they face inevitable uncertainty. Such pragmatism manifests when actors justify or critique the different political ‘grammars’, put forward by Boltanski and Thevenot (2006 [1990]) as ‘The Grammars of Worth’3. The GoW are scaffolded into categories of political philosophy: a market grammar, an industrial grammar, a civic grammar, an inspired grammar, a domestic grammar, and a fame grammar (Table 1). By deconstructing how organisations pragmatically negotiate, assemble, and partner alongside different political grammars, we can reduce them to the fundamentals of their varied work.

How might FPSC facilitate our understanding of foundation work in global policy? We show how in a case on the Alliance on the Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) – a partnership created by The Gates Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation, designed to shape African agrarian policy. Following FPSC’s logic that organisations should be deconstructed into interactions between actors, we highlight how foundations’ work takes place within a network of public and private projects. For example, funding for AGRA comes from the Partnership for Inclusive Agricultural Transformation in Africa (PIATA), which includes the Gates Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, and the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

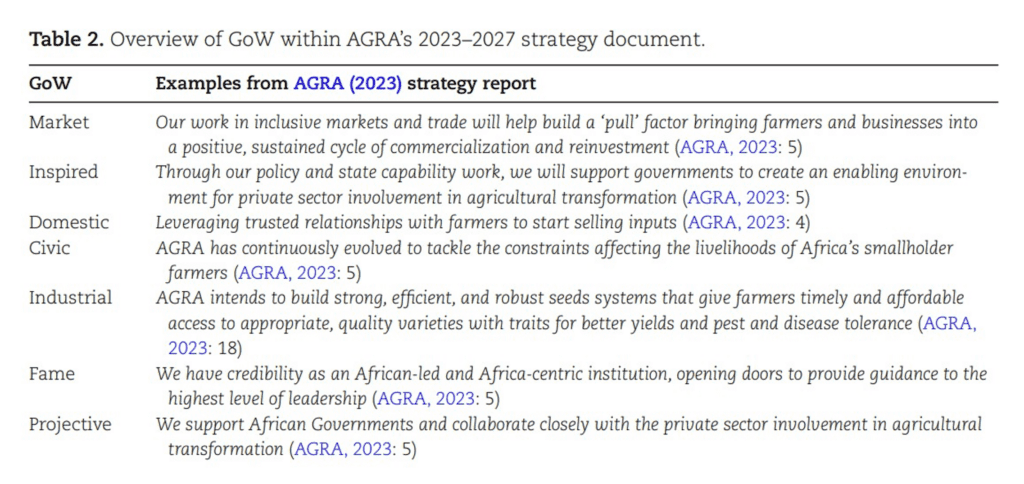

Further following the FPSC remit, we show how a variety of GoW manifest within AGRA policies, as evidenced in their 2023 strategy report (see Table 2). This suggests that foundations pragmatically justify their practices alongside a variety of political ideologies, as shown below. One example of this can be found in the agricultural policy of ‘leveraging trusted relationships with farmers [domestic grammar, based on trusting, familial relationships] to start selling [market grammar, based on buying and selling of goods] inputs, and our initiatives to strengthen last mile delivery systems [industrial grammar, based on technical efficiencies]. While scholarship has rightfully highlighted that market-driven ideologies softly transfer into policies, this example suggests what FPSC would call a ‘compromise formula’ of different GoW, whereby a common good beyond market value can transcend ideological differences. This also proposes that foundations package forms of policy that persuade different actors and groups, making their value proposition simultaneously justifiable and vague as they proverbially ‘sell’ their policy within the wider policy arena.

Finally, drawing on FPSC’s emphasis that actors use pragmatism to critique forms of work, our case on AGRA shows how critiques did and did not shape philanthropic policy. While AGRA showed some examples of internal critiques leading to policy change (evident in annual upgrades to their policies), more concerningly, however, are the critiques on AGRA from outside the organization that have not leveraged policy change. A damming evaluation from Mathematica that said AGRA has failed to meet its goals, petitions from grassroots farmers to end AGRA because it creates colonial forms of dependency, and a scathing takedown from Tim Wise out of Tufts University has not been publicly recognised by AGRA.

In fact, it appears that the only known time AGRA has bowed to external critical pressure was due to a legal obligation, when US Right To Know received previously undisclosed evaluation reports through the US Freedom of Information Act process. As we said in our paper, AGRA’s defusal of critique from various stakeholders ultimately reminds us of ‘who does and does not have an influential voice within the policy agora’.

Altogether, using FPSC to think about the organisational work of foundations (in this case, how foundations like Gates and Rockefeller partner with state actors on AGRA), we offer novel insights into the work of global philanthropic policy: foundations are endowed with an ideological pragmatism, foundations use political grammars to persuade the public of their worth, and foundations engage with and eschew forms of critiques that aim to mediate change. As we deconstruct foundations along these pragmatic lines, we can begin to uncover their theoretically-nebulous character by marrying interpretive and critical research offered by FPSC.

The full paper is Petzinger, J., Jung, T., & Orr, K. (2024) Pragmatism, partnerships, and persuasion: theorizing philanthropic foundations in the global policy agora, Policy and Society, 43(1), and is available as free open access online at https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puad016

Endnotes

- Collins, C., Hoxie, J., and Flannery, H., (2018) Warehousing Wealth: Donor-Advised Funds Sequestering Billions in the Face of Growing Inequality, Institute for Policy Studies

- Horvath, A. and Powell, W. (2020) “3. Seeing Like a Philanthropist: From the Business of Benevolence to the Benevolence of Business”. The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, Third Edition, edited by Walter W. Powell and Patricia Bromley, Redwood City: Stanford University Press, pp. 81-122. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503611085-006

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006 [1990]). On Justification: Economies of Worth (C. Porter, Trans.). Princeton: Princeton University Press

Featured Image: Photo by Brett Jordan